Today’s leadership spill curfuffle within the Liberal Party of Australia has again put politics and trust into sharp focus. It is a salient example that helps us understand why trust in politics – of all colours – is waning.

Public trust in leaders, in politics and elsewhere, is vital but difficult to sustain when leaders’ actions appear inconsistent, transactional and self-interested.

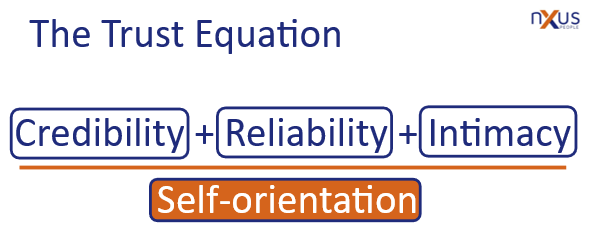

To dive into this subject, we can use the Trust Equation, which we apply with our leaders. This useful lens was first introduced in 2000 by Maister, Green and Galford in their book, The Trusted Advisor.

Trust = (Credibility + Reliability + Intimacy) ÷ Self-Orientation

It’s worth unpacking each element in relation to politics in general and reflecting on today’s political activity.

Credibility

Many politicians enter Parliament with strong professional backgrounds: law, economics, defence, medicine, and business. They bring real-world experience and expertise.

But credibility in politics is fragile. New MPs must quickly learn the complexities of Parliament—legislation, processes, negotiation, and party dynamics—while operating under constant scrutiny. At the same time, visible factional manoeuvring can make positions appear politically driven rather than principle-driven.

Credibility, therefore, isn’t just about qualifications. It’s about demonstrating competence within the system while remaining steadfast in clear values.

Reliability

Reliability is about consistency over time. Doing what you say will do. In complex environments, it can be about steadiness, clear direction, consistent signals, and follow-through.

Leadership spills, reshuffles and internal contests create a sense of instability. Even effective policy delivery can be overshadowed by a narrative of churn.

Intimacy

In the Trust Equation, intimacy is about people knowing one another.

Do I understand what this person stands for?

Do I have a sense of their character?

Are they predictable in their values, not just in their messaging?

When politicians and other leaders appear dominated by internal deals or career positioning, that sense of knowability can weaken. Leaders can feel like operators within a system rather than individuals with clearly anchored convictions.

Self-Orientation (the denominator)

This is where trust rises or falls most dramatically.

If behaviour appears primarily self-serving, preserving position, securing advancement, and consolidating power, perceived self-orientation increases. Because it sits in the denominator of the equation, even small increases can sharply reduce overall trust.

I don’t intend this reflection isn’t partisan. Leadership contests and internal negotiations occur across parties and across democracies.

But the leadership lesson is broader: When behaviour appears transactional and self-focused, trust declines.

When leaders demonstrate competence, steadiness and authentic character, trust strengthens.

Today’s politics simply makes the Trust Equation visible in real time.